And a smoothing plane is great for getting rid of the ridges left by the power plane and creating an event surface.

A little sanding to finish the job never hurts.

For the port side Tim, decided to do things the old fashioned way. There are few tools more rewarding to work with than a finely tuned hand plane. And just look at all those shavings.

Just a few more passed with the jointer plane to finish the job.

Nice.

Stepping back a little you get a nice look at what the finished taper looks like.

In addition to tapering the aft section of the keel, we're also working on laying out the rabbet. The rabbet is where the planking connects to the backbone. In a carved rabbet like the one we're doing on the catboat, a continuous notch is cut into the backbone to fit the planks where the two come together. Along it's entire length the rabbet is defined by two points: where the outside of the planking intersects the side of the keel (called the rabbet line) and the bearding line, where the inside of the planking and the side of the keel intersect. Before we can carve the rabbet, we must first have these two lines (rabbet & bearding) defined over the entire length of our backbone.

Luckily we already have the rabbet and bearding lines marked at numerous points along each of the individual pieces of the backbone. Now that they're all assembled, all we have to do is connect the points and check that everything's fair.

To get a fair line between all of our known points, we use a batten just like when we were working on the loft floor. But unlike in the loft we don't necessarily want to drive a lot of nails into the piece we're working on. We can eliminate most of the nails by using sticks to hold the batten at each of our points.

The sticks are cut to a point, so they work just like a nail would, defining the line at a single point. In a few spots we'll go ahead and use nails because we'll be carving away the material anyway.

The batten is carried all the way aft. In this picture we can see how the bearding line fairs in with the inner keel at the stern.

Because the rabbet determines where the planking falls on the backbone, we're careful to make sure that both sides are the same, especially at the stem where any irregularity will be especially noticeable.

Since we're aiming to have both sides be symmetrical, we're using a lot of points to define our curve at the stem.

The result? Looks fair from here.

As the lines run aft, it's just as important to make sure that they are hitting all the same points on both sides, but because the curve is much more graceful the batten doesn't need to be fixed in as many points.

Once our rabbet and bearding lines are laid out on the backbone, we're ready to start carving the rabbet. Rather than carving the rabbet continuously from stem to stern, we start by carving pockets every six to eight inches. The spacing of the pockets is closer together where the rabbet is changing a lot, and further apart where the rabbet is more constant. Once we've got pockets carved the entire length of the rabbet, we can go back and carve out the rest, fairing between the pockets. Here's a quick look at how it's done:

We start by defining our pocket. In order to keep a clean edge on the rabbet and limit tear-out, it pays to score the rabbet and bearding lines.

To determine the angle of our rabbet, we use a block that is the same thickness as our planking will be, known as a fid. While holding the inside edge of the fid on the bearding line (on the right in the picture), use another block, or any straight edge, to extend the outside edge of the fid to the rabbet line. Once the fid is angled so that the inside of the "plank" is on the bearding line and the outside is on the rabbet line, you've got the angle at which your planks will intersect the keel at that point.

Our pocket is then carved to allow the fid to be notched into the keel at the determined angle.

Once our pocket is carved, the outside face of the fid is touching the rabbet line and the inside face the bearding line. While the angle changes over the length of the backbone, determining that angle is done exactly the same.

Once the angle of the planking is determined using the above method, a bevel gauge can be used to "remember" the angle while carving as Tim is doing in the picture below.

Creating the rabbet is a little different at the inner keel. As you may remember an inner keel extends the back rabbet at the stern of our catboat. Along the rest of the length, we'll use cheek pieces to do the same thing. These cheek pieces will be installed after the rabbet is carved, but in the case of the inner keel, it has already been installed. To create the rabbet here, we use the same method to determine the angle of the planking, then using a rabbet plane, we can bevel our inner keel to match that angle.

Then using the inner keel as a guide, cut the rabbet.

There's still a little bit to go, but we'll wait till we've got the backbone on the building jig to finalize the rabbet.

When carving the rabbet, the first few pockets take a while...

But soon things go pretty quick.

Good thing too, 'cause there are a lot of them to do.

As we get most of the pockets carved, we can start fairing between them, and the rabbet starts to emerge.

For the most part we're not worried about the ends of our pockets tearing out, because the material's going to be carved out anyway, but at the top of the stem you definitely want a clean edge. This is where the top of the steer strake will come into the stem, so you don't want to see a lot of tear-out here.

Not too shabby.

As the rabbet runs up the stem it gets a lot deeper 'cause here the planks are coming in at a much steeper angle.

We've almost got the starboard side done all the way.

Here's a nice look at the rabbet running forward.

Once the rabbet is carved far enough, we can start installing the cheek pieces I mentioned earlier. These pieces will extend the back rabbet (the surface contacting the inside of the plank) providing a greater surface area for fasteners. We've already made up these cheek pieces, so they're ready to be fastened on.

The bottom edge that will form the back rabbet has been beveled to minimize the amount we'll have to do once we've got it on the building jig.

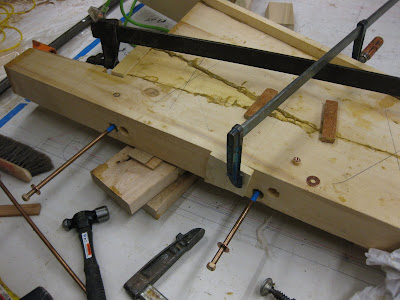

As with the other parts of the backbone, we're using bedding compound between the cheek and the keel.

A few adjustments here and there, and we fasten it on.

All that's left to do now is clean up the squeeze-out.

Looks pretty cheeky. (Sorry.)

With the rabbet carved to the top of the stem, all that's left to do is...

Flip it over and start on the other side.

It's the same operation as the other side, so things go pretty quickly.

And so our third week of the quarter draws to a close with the rabbet almost complete.

Carving the rabbet is a bit of a milestone in wooden boatbuilding, not to mention a lot of fun. And once the rabbet is carved, planking isn't far behind. But that's a story for another time. First, we've got to finish this rabbet.